Cork: A river runs through it

- Michael McCarthy

- Apr 22, 2021

- 12 min read

A series of mishaps and overspends on flood relief projects by the OPW call into question the agency's ability to deliver flood relief for Cork.

by Ellie O'Byrne

A bobbing Cork

Hey…what’s that? Did you feel it? Was that the ground...moving?

If you’re in the second city, it’s true. Cork, built on a lattice of waterways over marshland, and true to its name, is forever bobbing gently but imperceptibly on the tide.

“The pavements actually rise and fall a couple of millimetres with every tide cycle,” chartered quantity surveyor Michael McCarthy explains to me.

An associate of McCarthy’s, the geologist Anthony Beese, is writing a book in which data collected during survey reveals that Cork’s twice-daily rise and fall amounts to “a few millimetres.” More research is needed, but so-called “tidally-induced surface deformation” is a phenomenon that has been observed in other cities, Beese asserts.

And this is the reason why McCarthy believes the OPW’s contentious Lower Lee Flood Relief Scheme is “a really, really dangerous scheme.”

McCarthy and Beese are members of the Lee Engineering and Environment Forum (LEEF), the group, which also includes an architect and a chartered engineer, founded to study the viability of the Lower Lee Flood Relief Scheme.

Michael McCarthy visiting The Thames as it passed through London. Credit: Michael McCarthy

Their objections to the current plans by the OPW (Office of Public Works) for a series of flood defences along the course of the river Lee from Iniscarra through Cork city are many. And the safety and structural integrity of buildings is just one of them.

“Cork is built on a marsh and is very connected to its underground watercourses,” McCarthy tells me. “The plan is to put in pile cut-offs that will interfere with the groundwater regime in a way that we don’t know what the consequences will be. There has been no analysis or study of this at all. It is very, very scary. Particularly when you see buildings in Cork falling down.”

LEEF are not to be confused with Save Cork City, the campaign group which is currently taking both a High Court challenge against An Bord Pleanála’s planning go-ahead for flood defences at Morrisson’s Island, and a complaint to the European Commission against Ireland’s approach to flood defences.

“Our role is just to research, and point out the issues, which are significant and many in terms of costs, geological and engineering complexities,” McCarthy says.

Morrison’s Island, where Save Cork City are disputing flood relief works. Credit: Ellie O’Byrne

Nevertheless, both LEEF and Save Cork City have been in dispute with the OPW, as well as with local councillors keen to see flood defences go ahead to protect a city that floods with monotonous regularity.

The dispute is years old, and well-publicised.

The OPW asserts that their plam, which they estimate will cost €150 million ( LEEF and Save Cork City put this figure at €350m) is the cheapest and fastest way to protect the city.

But LEEF and Save Cork City favour a tidal barrier at Little Island, which they say will provide longer term protection from tidal flooding in case of sea level increases due to climate change, in conjunction with natural flood protection measures designed to slow down the flow of the river including upstream storage, to protect from fluvial flooding. The OPW say the cost of a tidal barrier would be €1 billion.

The debate about the River Bride, which I covered last time I wrote for Tripe + Drisheen, can be seen as a microcosm of the ongoing argument. In fact, initially, works to the Bride were included in the LLFRS.

As far as LEEF are concerned, the proposed flood relief works are “an experiment that’s likely to fail,” McCarthy says. Complex engineering, moving parts in need of maintenance, each constitute a stress point each time flooding occurs.

“We’re talking about 40 large pumping chambers, thousands of non-return valves,” he says.

“You have these over-engineered systems which are reliant on pumps and non-return valves, which fail. Their emphasis is to speed up the water in an area, which then causes more flooding in another area, which then requires a flood relief scheme in another area caused by what they’ve already done. They don’t look at a river in terms of a whole catchment. They need a whole-catchment approach.”

“They (the OPW) have a resistance to looking at any other form of flood defence other than hard engineering, which then causes other unforeseen issues downstream like sediment and bank erosion.”

A drainage act, and money

A “narrow, out-dated definition of what a river is is causing inordinate problems and expense. And it’s not even alleviating flooding in a lot of instances.

Part of the problem is, McCarthy tells me, the legislation covering the OPW’s flood defence programme. The Arterial Drainage Act of 1945 is a “narrow, out-dated definition of what a river is, which is causing inordinate problems and expense.It treats all our rivers as drains and not as vital ecosystems.”

The OPW was allocated €1 billion in funding for 118 flood relief projects in 2018, under the country’s national Flood Risk Management Plan.

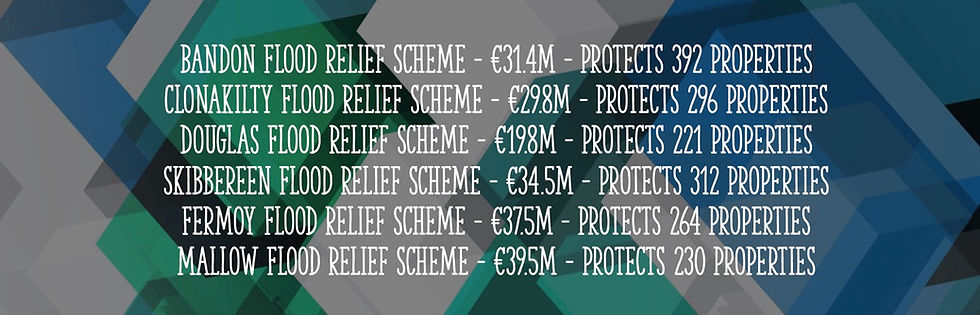

Sums of money involved are staggeringly vast. In County Cork, six schemes have cost the taxpayer €198 million to protect 1,715 properties in Bandon, Clonakilty, Douglas, Skibbereen, Fermoy and Mallow. That’s a spend of €110,000 per property.

Source: Gov.ie. Credit: Ellie O’Byrne

The fact that the OPW, who are responsible for maintaining Ireland’s public buildings and heritage sites, have been charged with the country’s flood management in the first place may be worth examining.

In November 2020, the OPW appeared before the Oireachtais’ Public Accounts Committee (PAC). Just a few weeks ago, Paul Murphy’s RTE investigation furthered revelations surrounding the agency’s finances, the derelict buildings they oversee and the sums of money involved in their undertakings.

Gross expenditure of €455.1 million was recorded for the OPW in 2019, according to the PAC. They hold land and buildings valued at €3.3 billion.

€99.3 million, or 22% of their total expenditure, was spent on the flood risk management programme.

But the PAC concluded that “the OPW did not have adequate contract monitoring mechanisms in place, especially in the types of work being undertaken.”

Overspends on flood relief are frequent and breathtaking. Bandon and Skibbereen, both controversial for other reasons we are about to look at, involved overspends of €7.5 million and €4.5 million respectively.

This is just one of the reasons why LEEF predict enormous overspends on the LLFRS, as well as on the entire Flood Management Plan.

“If they go over-budget at the rate at which they’ve gone over-budget on projects in Cork, they’re going to need a lot more than a billion,” McCarthy says. “All their projects are based on concrete and walls and sheet piling and they go over budget by several factors of the original tender. So I reckon they’ll certainly be going back to the well for more than that billion, at the rate they’re spending money.”

The Lee Flood Relief scheme is, there’s no doubt, the granddaddy of flood relief schemes, the single largest project to be undertaken.

Now, with various controversies, bungles and mishaps present in smaller schemes in the county, could public faith in the OPW to deliver such an irreversible and large-scale project be crumbling?

Is the OPW fit for purpose at all?

You had one job, fish pass…

Bandon represents, possibly, the biggest blunder of all.

During only its second winter of floods, a rock bed put into the river Bandon during the vast flood relief works - locals jokingly call the fish pass installed during the works, the largest in Europe, “the whale pass” - washed away this spring.

The result, local anglers have been horrified to observe, is that fish are now trapped, both above and below the ugly concrete structure.

Noel Baker at the Irish Examiner reported this week that the fish pass was “not done right and starting to fall apart,” but it’s actually far more serious than that.

The fish pass, whose entire reason for construction was to facilitate the movement of migrating salmon and sea trout, is now doing the exact opposite and actually trapping both young salmon parr and adults trying to migrate up the river to spawn.

This is a serious ecological catastrophe. It’s happening in the middle of the annual salmon run.

The Atlantic Salmon is, to our national shame, now listed as an endangered species. We have lost 60% of their numbers in just 40 years. Losing the salmon is not a matter of not being able to get good sushi: the king of fish also plays a vital role in maintaining the health of our rivers by acting as transport for freshwater mussels, the filter feeders once found in proliferation in Irish water systems, now, themselves, facing extinction.

Freshwater mussels are found in pristine river systems; they are extremely sensitive to things like silt pollution. In the 1980s, Ireland had 500 pristine river systems. Today, we have just 20.

A political career might last 40 or even 50 years. But a freshwater mussel, Ireland’s longest-living animal, will live to 140 years. They will filter over 2.5 million litres of water in their lifetime. But they’ve got to hitch that lift upstream from a salmonid. So the scarcity of salmon has huge knock-on impacts on river health.

“Yes, it’s a very serious situation,” Simon Toussifar, who is a keen fly fisherman from Kinsale who fishes on the Bandon river, says. “With less numbers of salmon coming back each year, the struggle for this species is to stay alive.”

Catch and release: Simon Toussifar. Credit: Simon Toussifar

Hearing that the fish pass was trapping fish in a round-robin email sent out by Bandon Angling Club in late March, Toussifar went to take a look for himself as soon as the Covid-19 5km travel limit was lifted, and videoed what he found.

“What I saw was a desperately sad situation,” Toussifar says. “The salmon parr pass on top of the dam area of the constructed fish pass had completely dried up, meaning salmon parr were unable to travel downstream. These juvenile fish need to travel downstream to make their way to sea where they migrate further up north to feed.”

Simon Toussifar’s image of the Salmon parr “pass”: the shallow channel in dry concrete at the centre of the image is supposed to allow juvenile Salmon to navigate downstream.

“I proceeded to walk along the side of the fish pass noting the serious lack of water on the dam side of the 130m pass. I finally came to the top of the fish pass to see a weir-type water flow obstruction and could understand straightaway why all fish species could not get past.”

“Remove the monstrosity”

Toussifar is furious. He wants immediate and drastic action.

“The OPW needs to remove the monstrosity known locally as the whale pass,” he says. “It’s overly engineered, doesn't fit with its surroundings and will more than likely encounter continued problems into the future. The Bandon had a much smaller fish pass for years that worked pretty well for salmon and sea trout before the OPW put in the new pass.”

His frustration with the situation dates back years: he, and many others, were horrified to witness the gravel river bed, a spawning ground and home for numerous species, being used as a highway by heavy machinery in 2018 during the contracted works.

“It was numbing to see rockbreakers and heavy machinery remove the river bed, leaving it a lifeless canal afterwards,” he says. “I hope I never see a river treated like that again. The OPW's flood relief program on the Bandon was an extreme, heavy engineering project and should never have been given the full go-ahead.”

Simon hopes that some of the damage to the river can be healed with time with the introduction of rewilding measures.

The fish pass fail must be doubly frustrating for people like ecologist Dr William O’Connor, who warned that fish would be trapped in this article in Green News in 2018.

River Bandon Flood Relief works: €34 million worth of environmental catastrophe. Credit: Simon Toussifar

The OPW have responded to the catastrophe, promising “emergency works” to be completed by May 1.

I’ve been promised an interview with OPW Minister of State Patrick O’Donovan, but unfortunately due to his busy schedule this couldn’t happen in time for this article: instead, I was issued a press statement promising to rectify the situation.

“In March 2021, the OPW became aware that the boulders, rock and gravel material that formed the bed of the ramp had deteriorated, possibly as a result of extreme flows in the river in February 2021. The OPW immediately carried out inspections, accompanied by IFI representatives and the fisheries’ specialist on the project,” the statement reads.

“The site inspections identified serious deterioration of the rock and gravel bed materials used in the construction of the fish pass, over its full length.”

“The situation is currently creating serious difficulties for various aquatic species in migrating over this newly exposed ‘step’ at the upstream end of the fish pass, particularly in low flows.”

An assessment screening in line with the Habitats Directive is now taking place, and a contractor being found for the emergency works.

Large concrete blocks

The proposed solution is not the same as Toussifar’s drastic action of removing the botched pass.

“The proposed solution will comprise of large boulders placed in a line across the width of the fish pass - close to the ‘step’ at the upstream end of the pass - to create a pool from which the fish can pass with greater ease,” the statement concludes. “The use of natural boulders is preferred, but if suitably sized boulders cannot be sourced, the use of large concrete blocks will be considered.”

You had one job

All these flood works have taken place with the understanding amongst local communities that flood defences would remove their watery woes, and would also restore the ability of locals to get flood insurance to protect their homes and businesses.

But two flabbergasting failures within the past year, in Skibbereen and Fermoy, have even called this outcome into question.

Last August, during Storm Ellen, Skibbereen, whose flood relief works have seen the Caol stream transformed from a meandering village watercourse into a concrete-lined open drain, flooded.

The drainage system was “overwhelmed” by the flood waters, Cork County Council’s engineer said. Delays relating to Covid-19 meant that some flood defence structures, including trash screens, were not installed in time for the big storm. The drainage system was “overwhelmed” by the flood waters, Cork County Council’s engineer said.

In Fermoy, the Blackwater - a serious contender for my personal favourite river - didn’t play ball this spring, flooding the town and causing the closure of Bridge St on t February 24. While Skibbereen’s flood defences did hold up in spring following last summer’s mishap, fluvial flooding in Fermoy, recently the beneficiary of €37.5 million for flood defences, gave rise to a report that found that a pumping station had failed.

While OPW Minister Patrick O’Donovan released a press statement Hailing Cork’s flood defences as a success this spring, serious questions remain.

Not least as to whether insurance companies will now play ball, once €110,000 worth of taxpayer’s money per insurable property has been pumped into flood defences.

Fermoy, Skibbereen, insurance…and demountables.

“We worked actively with the insurance federation and with the Department of Finance,” John Sydenham, Flood Risk Management chief with the OPW said during his PAC appearance last November. “The memorandum of understanding, to distill it down to its basics, is that once we provide schemes, the insurance industry provides insurance cover to property owners in the protected area.”

But insurance companies are baulking at ensuring demountables - the removable barriers that need to be manually installed to provide flood defences - Sydenham continued.

“The insurance companies, in a number of cases, have baulked at providing cover in areas protected by demountables because there could be an issue vis-à-vis the risks around human intervention, etc,” he said. “That has been in detailed discussions.”

“What I think is more important is that both we and the Department are going to be looking in detail at the actual level of protection. There are issues around whether everybody who should be getting insurance in the protected areas is getting it and there are differing views as to the veracity of some of the statistics that are available. There is work to be done in that area to make sure that we have hard data so that we can see the area that is being protected by a new system and all the properties. Then we should be a little bit more structured in finding out who is or who is not getting insurance cover in those areas.”

The LLFRS includes kilometres of demountables.

Demountable barriers on Sullivan’s Quay according to the LLFRS. Credit: LLFRS

Where do we stand: on solid ground, or on a marsh?

In County Cork, then, at least three projects in three towns, with a total spend of €103.4 million - the Bandon, the Caol in Skibbereen, and the Blackwater in Fermoy - have not even met their minimal requirements of surefire flood prevention and basic ecological protections.

The situation, Micheal McCarthy says, is “absolutely bonkers.” And it sets a precedence that calls the OPW’s fitness for purpose into question when it comes to the vast project that is the Lee flood defence.

“These are relatively small, isolated projects,” McCarthy points out. “In Cork, you’re looking at a multi-year project with challenging ground conditions.”

The over-engineering aspect - the pumping stations, valves, demountable barriers, fish passes - is not to be discounted. All come with an ongoing labour cost, and endless human resources issues. “Cork City Council took nine months to fix one non-return valve at Atlantic Pond,” McCarthy says.

Arterial drainage act..again

A very large problem, McCarthy believes, is that as public complaints mount, recourse is slim, due yet again to the Arterial Drainage Act. Transparency, and accountability on everything from fish pass failures to aesthetic vandalism to broken insurance assurances, is low.

“For the arterial drainage act, they do their own design and consultation,” McCarthy says. “They do a public consultation, then they give themselves ministerial consent, and then the project goes ahead.”

“There’s no independent cost-management function within the design team. So the cost is subordinate to design. There’s no cost accountability, no planning accountability, and no design accountability. The schemes are totally alien to their setting. Bandon has been absolutely destroyed: it looks war-torn.”

Only one question remains: should the OPW be handling Ireland’s flood defences at all, if you look at County Cork’s track record of the past two years?

“I don’t have confidence in the OPW to manage our rivers,” McCarthy says. “I think it would be done better by the EPA catchments programme. Or an entirely separate agency.”

Article published by Tripe + Drisheen:

Ellie O'Byrne: Cork: A river runs through it

Comments